Civil Rights Stories

The fight for civil rights in the United States is often associated with the Deep South, where marches, conflicts and court cases brought the movement to the forefront in the 1950s and 1960s. But more than 100 years earlier, a focus on civil rights emerged in Missouri.

Source: WUSTL Archives

An Early Call for Racial Equality

In 1819 — when Missouri was still a territory seeking to become part of the United States — free Black people and their white allies staged one of the first civil rights demonstrations on the North American continent. The protest centered on the Missouri Compromise, an agreement that allowed Missouri to join the union as a slave state in 1820. The decision amplified the conflict surrounding slavery in the U.S. — a conflict that ultimately led to the Civil War.

In the years that followed, events, individuals and legal decisions in the Show-Me State contributed to the advancement of civil rights.

Explore Missouri’s role in the fight for racial equality at locations across the state.

Missouri on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail

The U.S. Civil Rights Trail, which charts the course of the movement through 15 states and the District of Columbia, includes three sites in Missouri.

Dred Scott’s Fight for Freedom

Old Courthouse, St. Louis

One of the earliest and most significant court cases in the quest for civil rights took place at the Old Courthouse in St. Louis. The complex case began in 1846 when Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, filed suit for their freedom. After numerous appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1857 that because slaves were considered property, they did not have the right to sue.

While the family did not obtain freedom through their legal challenge, the case hastened the start of the Civil War, ultimately leading to freedom for all enslaved people in the U.S.

At the end of 2021, the courthouse began a major two-year renovation that will include new and updated exhibits. During this time, the grounds are open to visitors, but the interior of the courthouse is closed to the public.

The Decision to Desegregate

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library & Museum, Independence

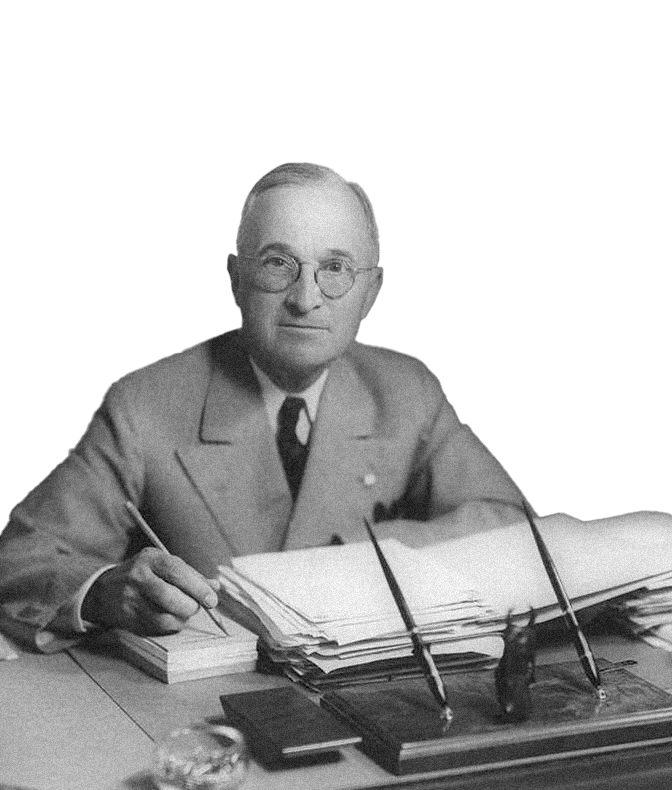

More than a century after Dred Scott began his fight for freedom, President Harry S. Truman was responsible for one of the country’s first political decisions in support of racial equality.

Truman, who was born in Lamar and lived much of his life in Independence, faced numerous challenges during his presidency — many related to the country’s role in World War II. In 1948, nearly three years after the war ended, he issued an executive order that desegregated the military and called for equal treatment for all persons in the armed forces, regardless of race, color, religion or national origin.

The order was considered a major civil rights victory and helped pave the way for desegregation in other segments of society.

Source: Library of Congress

Source: Library of Congress

Breaking Barriers Through Baseball

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City

When Jim Crow laws forced the segregation of organized baseball in the early 1900s, Black players formed their own baseball teams and leagues and traveled the country to play. The leagues included the Negro National League, established by several Midwestern team owners in Kansas City in 1920.

History was made in 1945 when the Brooklyn Dodgers recruited Jackie Robinson from the Kansas City Monarchs — one of the charter teams of the Negro National League. His Major League Baseball debut in 1947 was a key moment in baseball and civil rights history — and opened the door for integration in sports. Buck O’Neil, inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2021, also played for the Kansas City Monarchs and would go on to become the first Black coach in Major League Baseball.

The Negro Leagues eventually dissolved following the integration of baseball, but they left a lasting civil rights legacy.

Legal Challenges

Decades after the Dred Scott decision, the Missouri Supreme Court and U.S. Supreme Court ruled on several civil rights cases that originated in Missouri.

Source: Lincoln University Picture Collection, Inman E. Page Library, Jefferson City, MO

In 1938, Lloyd Gaines filed a lawsuit against the University of Missouri for denying him admission to the university’s law school. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor and ordered the university to either admit him or establish a law school for Black students in the state under the “separate but equal” doctrine in effect at the time. The Lincoln University Archives and Ethnic Studies Center, located in Jefferson City, features an exhibit about Gaines’ life.

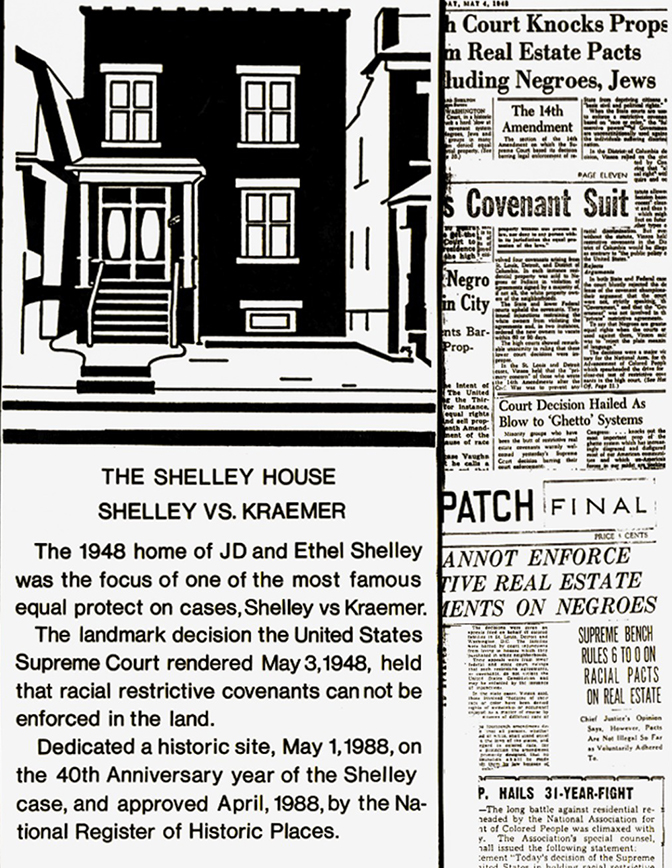

In 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer helped establish equal housing rights for Black citizens. The J.D. Shelley family had come face to face with discriminatory housing practices when they purchased a home in a racially restricted area of St. Louis. They filed suit, and after an extensive legal battle, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that enforcing racially restrictive housing covenants was unconstitutional. The Shelley House was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990.

A Quest for Freedom

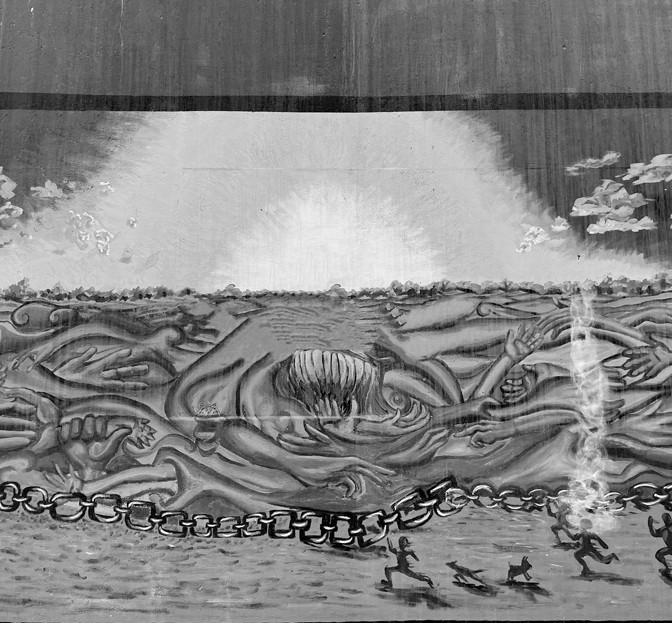

Missouri was home to one documented site on the Underground Railroad — a pivotal point that offered passage to Illinois where slavery was outlawed.

Abolitionist Mary Meachum helped dozens of enslaved Black people cross the Mississippi River to escape to freedom. Her efforts are honored at the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing in St. Louis. Charged with multiple counts of “slave theft,” Meachum was acquitted on one count, and the remaining charges were dropped. Located on the bank of the Mississippi River, the crossing point is Missouri’s only documented Underground Railroad site and is part of the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Educational Opportunity

Access to education was key to the advancement of civil rights — before and after the Civil War brought an end to slavery.

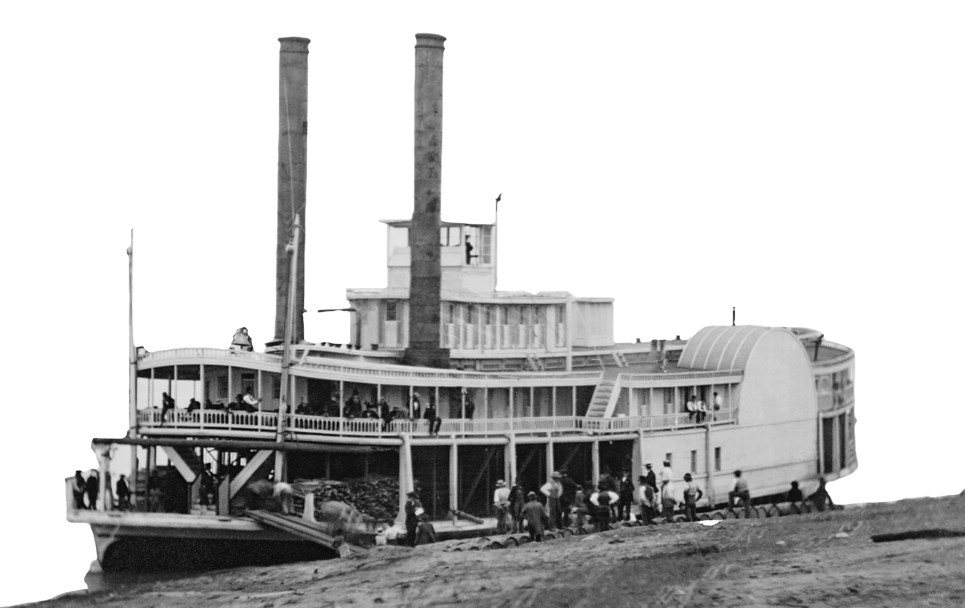

Like many states that allowed slavery, Missouri outlawed teaching enslaved individuals to read and write in the years prior to the Civil War. The laws were defied and learning occurred, primarily in secrecy. But Rev. John Berry Meachum, the founder of the oldest Black church in Missouri, boldly anchored a steamboat in the Mississippi River, equipped it with desks and chairs, and created the Floating Freedom School — outside of the state’s jurisdiction. The school provided an education for hundreds of free and enslaved Black students.

Source: Library of Congress

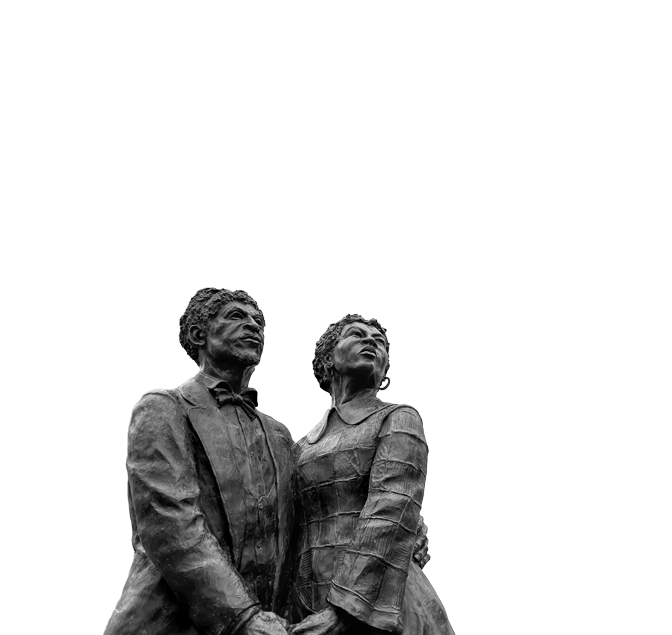

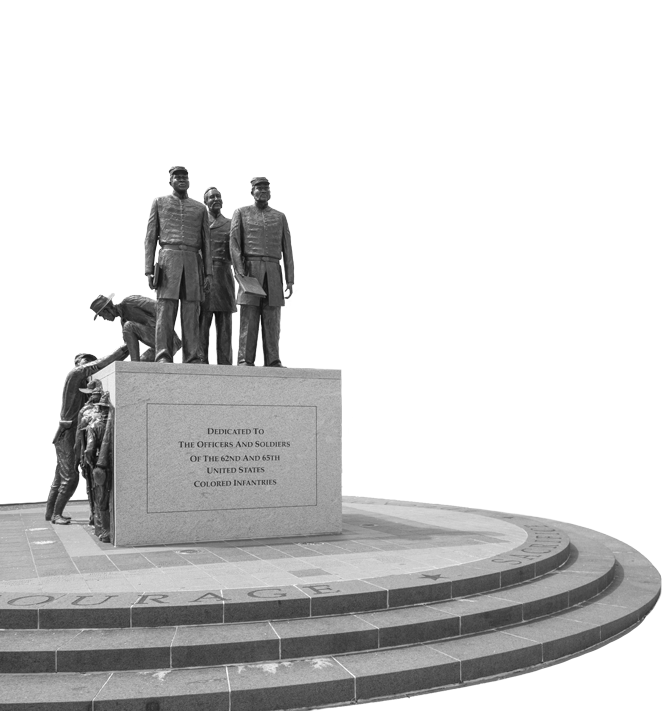

Lincoln University in Jefferson City was founded in 1866 by a group of Black soldiers who had escaped enslavement and joined the Union Army during the Civil War. Following the war, the soldiers — who had learned to read during their time in the military — pooled their money to establish the Lincoln Institute. The school eventually became Lincoln University, one of the first historically Black colleges in the country. The Soldiers’ Memorial Plaza includes a bronze statue that pays tribute to the soldiers’ efforts to provide educational opportunities to Black students.

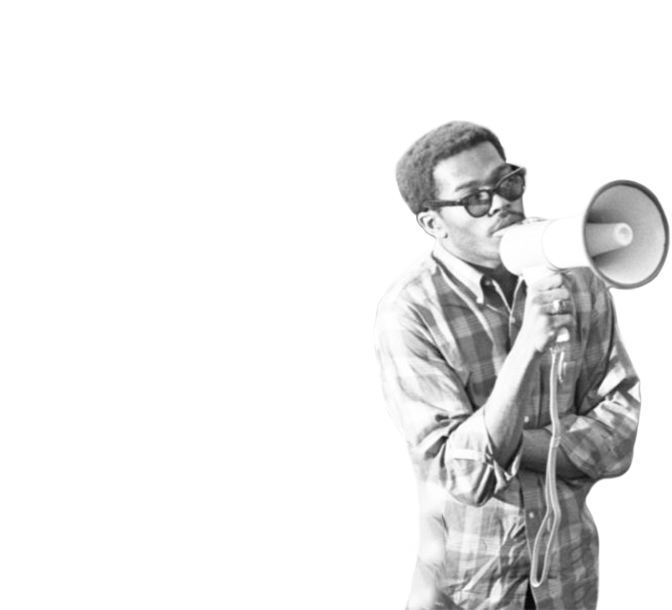

Speaking Out

Activists in Missouri used their voices, skills and talents in a variety of settings to call for an end to segregation and support for racial equality.

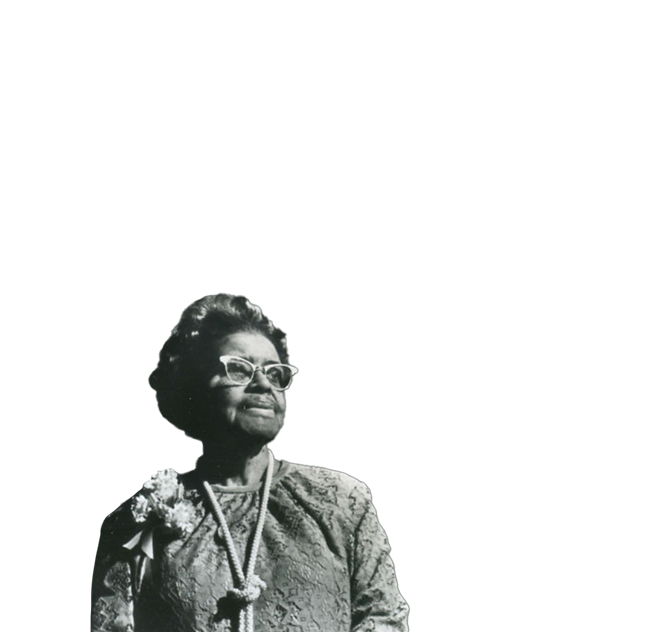

After initially being accepted into the Master of Journalism program at the University of Missouri in 1939, Lucile Bluford was denied admission based on her race. Seven years earlier, she had joined the staff at the African American newspaper, the Kansas City Call, where she worked 71 years as a reporter, editor, publisher and, ultimately, owner of the publication. Bluford spent much of her life and career advocating for integrated schools, fair housing and equal employment opportunities. Fifty years after applying to the University of Missouri, she was awarded an honorary doctorate degree.

Source: Hal Wells, Missourian Archives

Source: Missouri Historical Society

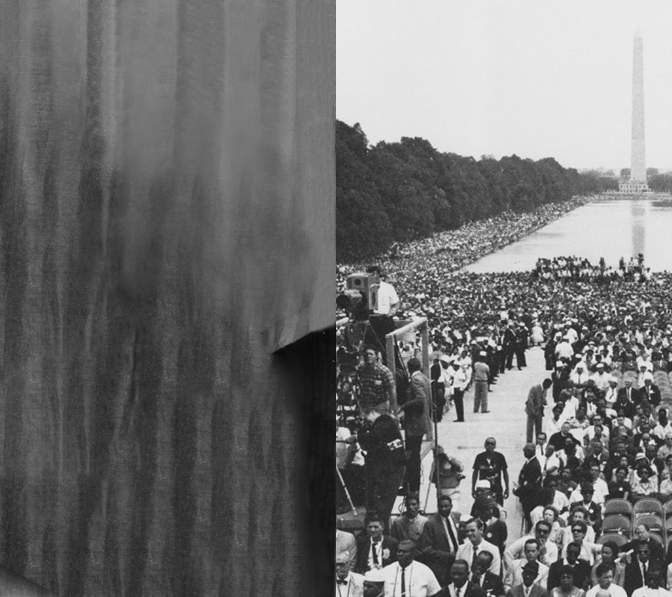

St. Louis native Josephine Baker is probably best known as a dancer and actress, but she was also a civil rights activist. Baker, the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture, refused to perform before segregated audiences. She worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and frequently wrote and spoke out in favor of racial equality. In 1963, she gave remarks alongside Martin Luther King Jr., at the March on Washington.

Protests and Progress

The fight for civil rights was fueled by increasing awareness and perseverance that propelled the movement forward.

St. Louis and Kansas City, like many American cities, had been segregated for decades when the modern civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s. The slow pace of reform and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. led to escalating protests and civil disorder. While some demonstrations turned violent, organizations such as the NAACP, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and other social action groups successfully led nonviolent protests and boycotts that spurred desegregation in public parks, hotels, restaurants and other places of business as well as increased employment opportunities and access to housing.

Source: WUSTL Archives